Chad Bryant: the complexities and contradictions of Czech nationalism under Nazi rule

CR: A vast amount has been written about the Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia during the German occupation, but we tend to focus on the more dramatic events – the occupation itself, the assassination of the Nazi ruler Reinhard Heydrich or the destruction of the villages of Lidice and Ležáky. But the American historian, Chad Bryant, has looked at the six years of occupation in an unusually nuanced way. His book Prague in Black looks at the complexities and contradictions of life at different phases of the occupation, as Czechs tried to hold their nation together and the Nazis dreamed of a German Europe. Chad Bryant is David Vaughan’s guest in Czech Books.

Chad Bryant, photo: David VaughanIt makes a change to find a book in English about the German occupation that is both erudite and highly readable. Chad Bryant, who teaches history at the University of North Carolina, lived in the Czech Republic in the early 1990s and speaks fluent Czech. This helps to explain why he is steeped in Czech history and why his book Prague in Black offers both deep and broad insights into what was going on in the occupied lands of Bohemia and Moravia during the occupation. The key question he tries to answer is how Czechs struggled to continue functioning as a nation, even after losing their political autonomy. The picture that emerges is a complex and shifting mosaic of defiance and collaboration, while German policy itself shifted from relative tolerance to brutal persecution. When I met Chad Bryant in a Prague café, he began our conversation with a joke – albeit a rather bleak one.

Chad Bryant, photo: David VaughanIt makes a change to find a book in English about the German occupation that is both erudite and highly readable. Chad Bryant, who teaches history at the University of North Carolina, lived in the Czech Republic in the early 1990s and speaks fluent Czech. This helps to explain why he is steeped in Czech history and why his book Prague in Black offers both deep and broad insights into what was going on in the occupied lands of Bohemia and Moravia during the occupation. The key question he tries to answer is how Czechs struggled to continue functioning as a nation, even after losing their political autonomy. The picture that emerges is a complex and shifting mosaic of defiance and collaboration, while German policy itself shifted from relative tolerance to brutal persecution. When I met Chad Bryant in a Prague café, he began our conversation with a joke – albeit a rather bleak one.

“One of the first things to consider is what the possibilities for action were. There was a joke after the war. A Czechoslovak member of the underground was speaking with a member of the Polish underground. The Pole says, ‘During the war we blew up bridges, we cut off supply lines, we assassinated Nazi leaders and so forth,’ and the Czech underground member says, ‘Well, that’s great! That was completely forbidden where we were!’ But in all fairness, it’s also a question of possibilities. The comparison that implies is rather unfair.”

I remember talking to a Polish historian, who reminded me that Poles were never given the opportunity to collaborate, because the Germans and the Soviets decided between them to carve up Poland and that there wasn’t going to be a Polish collaborationist government. Otherwise maybe things would have been very different, even there.

“That’s absolutely true. I think the context is important, if you think about the disappointment of Munich and the ugliness of the Second Republic…”

You’re referring to the Munich Agreement of September 1938 and then the rump republic which struggled on for the six months after that…

“It was rightwing in many ways and sought to protect its autonomy, but eventually it fell on March 15 1939.”

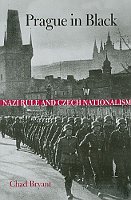

Photo: Harvard University PressThe Second Republic is often portrayed as having been still an independent Czechoslovak state, but in many ways it was not. It was totally dependent on Germany. The disillusionment that came with the Munich Agreement, with the secession of the Sudetenland and the collapse of Masaryk’s democratic republic was so enormous that it was already a broken fragment.

Photo: Harvard University PressThe Second Republic is often portrayed as having been still an independent Czechoslovak state, but in many ways it was not. It was totally dependent on Germany. The disillusionment that came with the Munich Agreement, with the secession of the Sudetenland and the collapse of Masaryk’s democratic republic was so enormous that it was already a broken fragment.

“Absolutely. It was a broken fragment and the defences had been wiped out by the Munich Agreement because the peripheries of Czechoslovakia had been absorbed into Germany. It was very clear that the Second Republic was within the Nazi sphere of influence. Every effort was made to try to preserve as much autonomy as possible. One can argue that the then President, Emil Hácha, took on this attitude and this attitude continued even throughout the occupation, after March 15 1939.”

One thing that does come as a surprise to many people when they read about the period of the Second Republic is the extent to which anti-Semitism suddenly reared its head.

“This is not just a Czech trend. This was all over Europe – the emergence of anti-Semitism and the emergence of right-leaning governments that were either satellite states or collaborated, or seemed poised to accept a Europe in which Germany was dominant and in which democracy was no longer an acceptable form of government and where corporatism as an economic system was paramount. So the rise of anti-Semitism was part of a larger European trend and the Second Republic did institute various pieces of anti-Semitic legislation. The organization of doctors, for example, forbade Jewish doctors from practising anymore, anti-Semitism reared its head in the newspapers. It is a question of why. Was it the disappointment and disillusionment that led to looking for scapegoats? It continued throughout the war, sadly.”

It is strange how the Second Republic changed almost seamlessly in the middle of March 1939 into occupation, when German troops marched into the country unopposed and Slovakia, the day before, declared independence. It’s a warning of how easily a country can slip within months from being a more-or-less functioning democracy into being a vassal state or an occupied state.

“I think that’s right. Hitler and those around him, at least at that moment, wanted it to be as seamless as possible because they believed that the war industry within the lands that became the Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia was so crucial. They needed the Czech government, they needed President Hácha, they needed the civil servants to keep working, they needed the police to maintain order, they wanted a smoothly functioning society that would enable to war machine to keep going.”

Emil Hácha meets Adolf Hitler in Berlin in 1939, photo: Bundesarchiv, B 145 Bild-F051623-0206 / CC-BY-SA 3.0Which brings us to the subject of your book, Prague in Black. I find the idea that you put forward very interesting: that there are two sides to what happened. The tragic side is that Czechoslovakia was able to slide so easily into German control. The other side is that this did mean that after the occupation there were probably more opportunities for national self-expression than there were in most of the countries that were occupied by Germany, because of this desire among the Germans to keep things flowing smoothly.

Emil Hácha meets Adolf Hitler in Berlin in 1939, photo: Bundesarchiv, B 145 Bild-F051623-0206 / CC-BY-SA 3.0Which brings us to the subject of your book, Prague in Black. I find the idea that you put forward very interesting: that there are two sides to what happened. The tragic side is that Czechoslovakia was able to slide so easily into German control. The other side is that this did mean that after the occupation there were probably more opportunities for national self-expression than there were in most of the countries that were occupied by Germany, because of this desire among the Germans to keep things flowing smoothly.

“What surprised me most during my research, when I was getting into the archives and keeping an open mind on what I saw, was that many people, even after the war, saw the first six months or even nine months of Nazi rule as one of the greatest moments in national history. Many people had been disappointed by the political infighting of the interwar period, of the First Republic; they had been disappointed by the Munich Agreement and the ugliness of the Czechoslovak government.”

So, you’re saying that there were many people who actually saw the first collaborationist government after the occupation as a functioning government that genuinely was enabling the Czech nation to thrive.

“The idea was to nurture national feeling and nurture a new national culture and to turn away from politics as it had been understood in the interwar period, and to turn in some ways to the 19th century. There were calls that this could be a new 19th century in which the cultivation of a national feeling and moral fibre could take place below – or outside – official politics. And there was a belief that the Nazis would allow them to do that.”

I know that in the early part of the occupation there was a great deal of Smetana being performed – as the national composer – and there was a strong cult of Saint Wenceslas, which also suited the Germans because he could be interpreted as somebody who made peace with the Germans.

German soldiers in Prague in 1939, photo: Public Domain“That’s right, and there were various attempts by Nazi propagandists to try to create a history that would allow this Czech national history to exist, while still accepting Nazi rule – things like Saint Wenceslas or recalling the Holy Roman Empire and Charles IV. Of course, there were also underground organizations that came together at this time and were seeking, if not to overthrow Nazi rule, at least prepare for a day in which Nazi rule would end.”

German soldiers in Prague in 1939, photo: Public Domain“That’s right, and there were various attempts by Nazi propagandists to try to create a history that would allow this Czech national history to exist, while still accepting Nazi rule – things like Saint Wenceslas or recalling the Holy Roman Empire and Charles IV. Of course, there were also underground organizations that came together at this time and were seeking, if not to overthrow Nazi rule, at least prepare for a day in which Nazi rule would end.”

What might also surprise many people is the fact that the collaborationist government in Prague under Alois Eliáš was secretly in touch with the Czechoslovak government in exile in London.

“That’s right. They were. Eliáš especially. And Hácha, the president at the time, knew about it. Others didn’t know. Hácha himself spoke quite eloquently about how he was sacrificing himself in many ways for the nation.”

But at the same time the foundations were being laid for the Holocaust. Life was becoming increasingly difficult for Jewish Czechs.

“The Nuremberg Laws were introduced by the new Reichsprotektor Konstantin von Neurath shortly after the occupation began. And then a cascade of decrees began, preventing Jews from shopping during certain days of the week, preventing them from going to theatres, excluding them from various professions. I don’t want to paint too rosy a picture. There were also elements who became willing collaborators: especially Czech fascists offered themselves as informers to the Gestapo and the Sicherheitsdienst, the SS intelligence service.”

You suggest that there was a status quo in the first months of the occupation which – under the circumstances and with the exception of those who were Jewish – more or less suited both the Germans and the Czechs. So why did that change? Why did Reinhard Heydrich come as Deputy Reichsprotektor, replacing von Neurath and introducing a far tougher regime?

“The organization of the Sicherheitsdienst and the Gestapo became much better, much more coordinated. They actually obtained offices, they cultivated informers and denunciators in the population, the numbers of which grew over the years, and eventually this web of terror became more and more strict over time.”

Reinhard Heydrich, photo: Bundesarchiv, Bild 146-1969-054-16 / Hoffmann, Heinrich / CC-BY-SA 3.0Reinhard Heydrich was also one of the key figures in forging the racial and racist policies of the Third Reich. He had outlined plans for the various Slav nations, including the Czechs. This included the idea that half the population could be in some way Germanized and that the others would be “removed” – whatever that meant. Was that threat real?

Reinhard Heydrich, photo: Bundesarchiv, Bild 146-1969-054-16 / Hoffmann, Heinrich / CC-BY-SA 3.0Reinhard Heydrich was also one of the key figures in forging the racial and racist policies of the Third Reich. He had outlined plans for the various Slav nations, including the Czechs. This included the idea that half the population could be in some way Germanized and that the others would be “removed” – whatever that meant. Was that threat real?

“Oh yes. That was absolutely real. There was a constant tension among Nazi leaders, even in the mind of Reinhard Heydrich – and perhaps even Hitler as well – between very practical on-the-ground needs for the various industries in the Protectorate to keep functioning to support the war effort and on the other hand entirely ideological dreams of creating a German-dominated Lebensraum in Central Europe. This included plans that began being drawn up in the spring of 1940 that included the expulsion of nearly three million Czechs and the forced assimilation of those who remained. This was actually approved later that year. When and how it was going to be realized was unclear, but when Heydrich came, one of the first speeches he gave to noted Nazi leaders in Prague was about his determination not just to realize the Germanization of the Protectorate but also all of Europe.”

And one of the things you discuss is the influence that this Nazi policy had on the subsequent events at the end of the war, after the liberation, when the great bulk of the German-speaking population of the lands of Bohemia and Moravia were expelled.

“The point I try to make in the book is that before 1939 being a Czech or a German was something that someone chose. You could choose your nationality in the sense that you could choose to belong to a Czech or a German association – or both – you could choose for the most part – not always – which school you would send your children to, which political party you would join. These were all public displays of nationality that were born of the Habsburg era, but during the Nazi era it was the first time that nationality became something marked on your identity papers, and this very idea of nationality was also something that Nazi leaders were beginning to try to impose through racial testing and other efforts to decide who would be assimilated or not. And the larger point of the book is that after the war it was no longer a choice of who was Czech or German. It was again determined by the state, by the Czechoslovak state. Nationality was for many people, especially those who were bilingual, a choice of a sort, and this choice was gone and hence something that was fundamental to the region’s history disappeared along with it.”

Do you think that the prehistory of the expulsion of the Sudeten Germans should be taken as a factor not necessarily in justifying the excesses during the expulsion but as a way of having a greater understanding for why and how it could happen?

Expulsion of the Sudeten Germans, photo: Sudetendeutsches Archiv / CC 1.0 Generic“I think that’s right. I think it’s time to move beyond the binary finger-pointing, the binary arguments about justifiability or unjustifiability. Since the 19th century our job as historians has been to try to understand and less to judge.”

Expulsion of the Sudeten Germans, photo: Sudetendeutsches Archiv / CC 1.0 Generic“I think that’s right. I think it’s time to move beyond the binary finger-pointing, the binary arguments about justifiability or unjustifiability. Since the 19th century our job as historians has been to try to understand and less to judge.”

Do you think there are still certain taboos in the study of Czech history here within the Czech Republic?

“I think there could be a lot more done on just what I was talking about – through the everyday experiences, beyond what people ate or the food rations they got, the actual experience of occupation itself. Instead we tend to concentrate on Heydrich and on collaborationist figures such as Hácha; we’ve done a wonderful job of unravelling the details behind the expulsions of the Sudeten Germans or the details of Heydrich’s rule – we know a great deal about his assassination – but far less about the actual experience of the occupation and how this affected Czech culture and how its impact on Czech culture and habits didn’t just go away in 1945. People were transformed by this in ways that we don’t really understand. These historical experiences don’t go away. They linger.”

David Vaughan