Pervetin remains major problem in Czech Republic

CR: On Tuesday, the European Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction released its European Drug report for 2014, mapping trends in illicit drug use and related threats to public health. For the Czech Republic, the news is sobering but not altogether surprising: that the country has the highest rate of methamphetamine consumption in Europe.

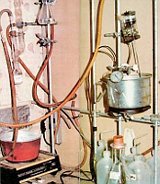

Photo: Filip JandourekIn the Czech Republic, it’s called pervetin: a psychostimulant, fairly easily produced, which gained in popularity among users in the former Czechoslovakia in the 1970s and continues to be popular among drug users in the Czech Republic today. Each year, the police uncover only a fraction of the six tonnes produced domestically and users have become increasingly visible in major areas, including Prague’s Wenceslas Square. Aleš Herzog of Sananim, an NGO helping people with drug addiction, estimates that the square sees traffic in the hundreds each day.

Photo: Filip JandourekIn the Czech Republic, it’s called pervetin: a psychostimulant, fairly easily produced, which gained in popularity among users in the former Czechoslovakia in the 1970s and continues to be popular among drug users in the Czech Republic today. Each year, the police uncover only a fraction of the six tonnes produced domestically and users have become increasingly visible in major areas, including Prague’s Wenceslas Square. Aleš Herzog of Sananim, an NGO helping people with drug addiction, estimates that the square sees traffic in the hundreds each day.

“Over the last 20 years, the centre of the drug scene boiled down to the most central location and most immediate hub, which is here. Nearby are public washrooms for a few crowns and nearby parks… Over the course of the day you get between 500-800 people walking up and down Wenceslas Square, from Muzeum to Můstek, asking ‘What have you got?’, ‘What do you need?’.”

Wenceslas Square, photo: Kristýna MakováOne change since the 1990s, Czech TV reported, is that low-level dealers today are often themselves addicts, making the problem even more conspicuous. And the problem is real: according to the annual study by the European Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction, the country has some 31,000 users, addicts who snort, smoke, or inject pervetin on a regular basis.

Wenceslas Square, photo: Kristýna MakováOne change since the 1990s, Czech TV reported, is that low-level dealers today are often themselves addicts, making the problem even more conspicuous. And the problem is real: according to the annual study by the European Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction, the country has some 31,000 users, addicts who snort, smoke, or inject pervetin on a regular basis.

Likewise illegal production is booming and even in joint police raids with German counterparts, Czech police bust only a fraction of gangs, and confiscate only a fraction of methamphetamine produced each year. While changes in legislation made it theoretically more difficult for producers to get a key ingredient (pseudoephedrine found in flu medicine), in reality it is easy to get, for example in neighbouring Poland where no limits no quantity are imposed. The problem appears only likely to get worse.

Curiously, while pervetin dealing is fairly visible in Prague, strategies elsewhere have changed. Visiting Ostrava and Cheb on opposite ends of the country, Czech TV learned that the sale and as well as use of the drug had moved largely behind closed doors. In Ostrava, from an outside location to privately-owned apartments, while in Cheb, one local suggested, certain gambling venues were more than they seemed.

Curiously, while pervetin dealing is fairly visible in Prague, strategies elsewhere have changed. Visiting Ostrava and Cheb on opposite ends of the country, Czech TV learned that the sale and as well as use of the drug had moved largely behind closed doors. In Ostrava, from an outside location to privately-owned apartments, while in Cheb, one local suggested, certain gambling venues were more than they seemed.

“They have cameras out front and can see if they know the person [and them in].”

As for remedies to the problem? Most would point to prevention programmes and educative strategies as one of the most important steps. There the study has found the situation lacking: in recent lean financial years (in the Czech Republic concretely in the years 2009 and 2011) it was precisely prevention programmes which were scaled back.

Jan Velinger